I am having too much fun fleeing my WordPress instance for Eleventy. I am impressed with how quickly I have already managed to put together some classic Mac OS-inspired pages. I’m working on getting the blog mechanism to work with the templates next, but that will take a while. So in the meantime, I will Sally Forth with my existing blogging rig and continue the themes I touched on in my previous post.

Setting the Scenario: Renewing Social Benefits for an Elderly Relative

My last post was freshly inspired by the frustration I am having renewing Medicaid coverage for an elderly relative. For those who have not had the pleasure of renewing Medicaid, for themselves or for someone else, there is an inherent amount of friction baked into the process that can often lead to unnecessary denials for those who qualify. For those with the time and resources necessary to navigate the system, it’s an exhausting endeavor. For those without the time or resources necesssary to navigate the system, it is often completely prohibitive.

I want to introduce you to the agents and workflows typically involved in this kind of Medicaid scenario.

Defining the Agents and Agencies in our Scenario

Principal – I’m borrowing this legal term to define the person on whose behalf the agent is working for. In the context of workflows we’ll discuss, they are typically a relative who is unable to manage their own affairs.

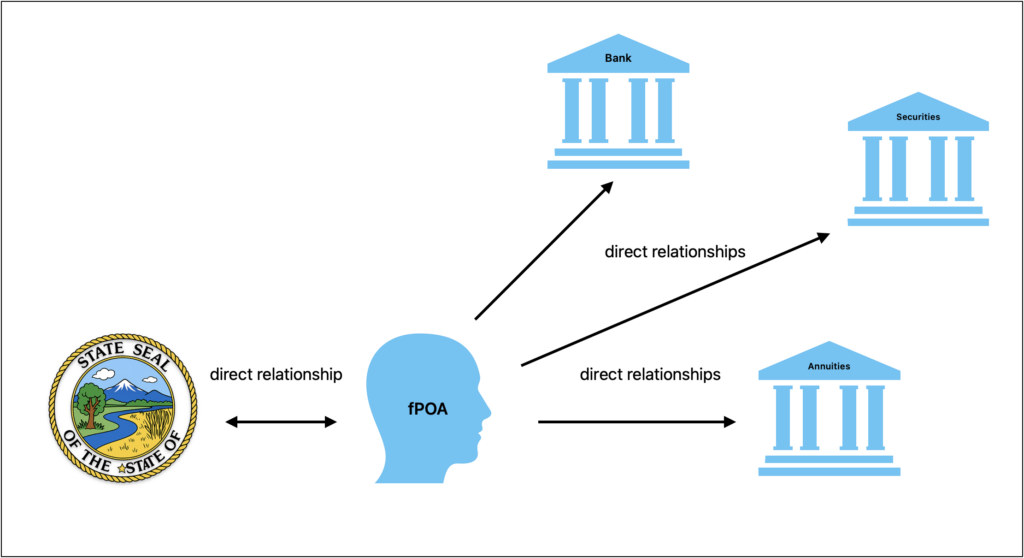

Agent – The agent is the person authorized to act on behalf of the principal. Authorization is provided in the form of a letter granting Power of Attorney (POA). There are typically two types of POA: Medical and Financial. Medical POAs (mPOAs) are given the authorization to make medical decisions on behalf of the principal. Financial POAs(fPOAs) are given the authorization to make financial decisions on behalf of the principal. I’m focusing the scope primarily based on my experience as a Financial POA (fPOA).

State Agency – States are typically given the jurisdiction of running their State’s Medicaid program. When initially applying for Medicaid, another agency such as an Assisted Living Facility, may reach out the State agency to put the State Agency in touch with the fPOA. (Experiences differ from State to State – your mileage may vary).

Medical Agencies – These are the medical agencies relating to the Principal. I have a main agency I work with, the Assisted Living Facility, but I also have to work with other medical providers as well. Your experience coordinating medical agencies may vary as well.

Financial Agencies – The financial agencies relating to the Principal. These are your typical financial retail products and services: banks, annuities, but you will also have to research and establish direct relationships with retirement benefits or other stocks and dividends. You also have to take into consideration other assets such as pre-paid burial plots.

Now that we know the agents, how do they interact? How do they even meet?

Simplified Agent Workflow

When the Principal’s Medicaid application is up for renewal, the fPOA is typically contacted by the State Medicaid agency. The State agency provides the fPOA a checklist of updated financial documents necessary for the Medicaid renewal. This checklist is usually a list of specific financial documents, such as updated statements, from various agencies.

As such, the fPOA must often reach out directly to each of the Principal’s financial institutions for updated documents. Each of these agencies has differing processes for authorizing and working with fPOAs, but rarely is the workflow online. And when it is online, it is often problematic for agents – I will explore this topic later. I will put a pin in it for now.

The fPOA and the State agency may be in direct touch, often via secure email. In that relationship, there is usually a responsive two-way interaction. The fPOA’s relationships to the various financial agencies, however, are often more “analog” and one-directional.

Most financial agencies, for example, require you to authorize – by phone – for each individual document request. Sometimes they ask you to resubmit Power of Attorney documents with each outreach. Often these requests are only fulilled by mail or even fax.

I want to walk through a workflow for obtaining one item on the State’s checklist, a financial letter from an annuity agency. As I describe these workflows, imagine how a generative AI agent would handle the same task. Bear in mind, this is only one item on the checklist provided by the State agency – for now we are not going to consider how a generative AI agent would manage the entire checklist.

A Simplified Workflow – Requesting a Current Financial Letter

I’ve outlined a typical set of steps involved for an fPOA to contact a financial agency for a checklist item. In this case, we are requesting an updated financial letter from a retirement annuity holdings agency. What is described below is an optimal scenario, where nothing goes wrong. Ideally, most of this would happen over a phone single call but, depending on the agency, these steps might stretch out over days.

- Agent calls financial agency and declares POA status tand follows authorization process

- Financial agency confirms fPOA authorization

- Agent requests updated financial letter

- Financial agency confirms financial letter is being sent in the mail

- Agent notifies State agency that checklist item will arrive within 3-5 business days

- Financial letter arrives in the mail

- Agent scans and sends financial letter to State agency

This is just one workflow for one item on the checklist provided by the State agency. For this one workflow alone, you can see a number of barriers for a potential generative AI agent:

- How does the generative AI agent work out the steps involved for each item on the checklist (phone, online)?

- Assuming the agent is able to navigate a phone conversation, what mechanisms exist that allow the financial agency to authorize the generative AI agent?

- Can generative AI agents check the mail? Or at least, can generative AI agents follow up with a human after several days?

- Assuming the generative AI agent can handle the entire checklist from the State agency, can it keep track of the details for each task, how they relate to each other, and communicate only the pertient information to each of the parties in a secure manner?

My goal is not to denegrate the concept of digital agents. I do not think generative AI models are the best foundation for building digital agents. I believe generative AI models will play a part in enabling digital agents, namely as a natural language interfaces and specialized models, but the bulk of the foundational work for trustworthy digital agents will be in building robust, deterministic systems and web infrastructure. I also contend that this infrastructure can enable many of features we want from digital agents at a fraction of the cost of building with a generative AI-model first approach.

What I am proposing is not a new idea so much as a return to the original vision for digital agents. Sir Tim Berners-Lee proposed in 2001 public Semantic Web infrastructure as being the technology that would enable digital agents to work autonomously. The reason I suggest we revisit this original vision of the Semantic Web is that, nearly 25 years on, with AI hallucinations and misinformation rampant, this original vision is more prescient than ever. Lastly, I propose that, as we build out Semantic Web infrastructure for digital agents, it can make the web more easily navigable for humans in the process.

The analogy I want to use for this Semantic web infrastructure are the visible effects of the American with Disabilities Act of 1990 on the design of public spaces in America. The design sensibilities that enabled greater accessibility for the disabled in public spaces (such as ramps and automatic doors) proved to have beneficial impacts for the greater society at large. I believe that Semantic Web infrastructure that we build to enable Trustworthy AI can reap dividends for the wider population beyond its initial stated scope. In short, I believe building Semantic Web infrastructure can be other example of universal design, with broad public benefit.

In the next article I want to call attention to the work that’s already been done to build out this Semantic infrastructure and demonstrate how it can be leveraged by agents, human and digital, to reduce friction.

If you have been reading this far, thank you. Feedback, as always, is welcome.